我覺得WSJ這樣搞很不行啊,搞成了CCP木偶啊!

《华尔街日报》解雇了四面楚歌的记者

最近几周,香港和中国的官方媒体指责香港记者协会破坏了香港的稳定。

4分钟

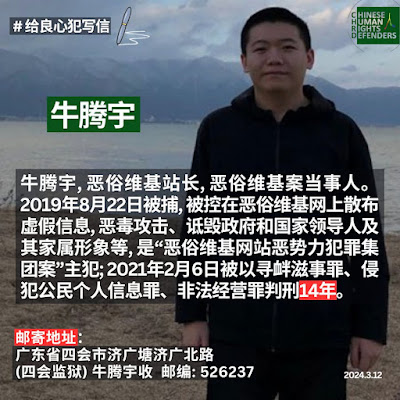

香港记者协会(Hong Kong Journalists Association)新当选主席郑秀莲(Selina Cheng)周三在香港与《华尔街日报》(Wall Street Journal)的雇佣合同终止后,向记者发表了讲话。 (Tyrone Siu/路透社)

由Shibani Mahtani

更新于美国东部时间2024年7月17日上午8:28|发布于美国东部时间2024年7月17日上午7:52

《华尔街日报》的一名驻香港记者在她当选为香港记者协会主席后不久就被该报解雇。

最近几周,香港和中国的国家支持和国营媒体指责香港的新闻宣传协会破坏了香港的稳定。

记者Selina Cheng周三在新闻发布会上表示,她认为终止与她作为该组织主席的角色有关。 她说,她受到雇主的压力,要求她退出协会。

郑汝桦说,在香港JA选举前一天,她的上司指示她撤回候选资格,并离开香港JA的董事会,她自2021年起一直是该董事会的成员。 她拒绝了他们的要求。

“[我]立即被告知这与我的工作不相容,”程说。 “编辑说,该杂志的员工不应该被视为在香港这样的地方倡导新闻自由,即使他们可以在西方国家,在那里它已经建立。”

香港联合行政会议被认为是一个工会,根据香港法律,成为工会的官员是合法的,这是《基本法》所保障的权利。

📰

关注媒体行业

“华尔街日报”母公司道琼斯(Dow Jones)的发言人在电子邮件回复中证实,该公司周三进行了”人事变动”,但表示无法对具体个人发表评论。

发言人补充说:”《华尔街日报》一直并将继续在香港和世界各地大力提倡新闻自由。”

如果与郑和在香港联合行政局的职位有关,这将是最新的迹象,表明即使是大型、资源充足的国际媒体机构也对在香港经营的风险持谨慎态度。香港曾经是一个自由自在的城市,在镇压包括新闻自由在内的公民自由方面,越来越像中国大陆。

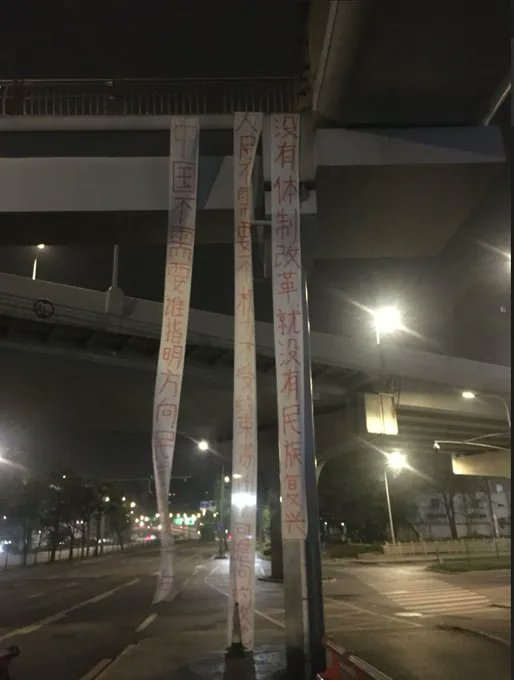

在2019年大规模抗议活动之后,北京在香港通过了一项国家安全法,该法对模糊描述的罪行(如颠复国家政权和与外国势力勾结)判处最高无期徒刑。

这些法律,加上今年通过的一系列以国内为重点的国家安全法,已经改变了香港的每一个机构,从法院到大学和新闻编辑室。 《国家安全法》通过后,《纽约时报》将其香港数字业务迁往首尔,称这些变化对其运营和新闻业意味着什么”存在很大的不确定性”。

今年早些时候,”华尔街日报”表示,它正在将其亚洲总部从香港转移到新加坡,并解雇了一些驻香港的记者。 程的角色在当时没有受到影响,她继续在城市工作。 32岁的Cheng报道了中国汽车行业,该杂志称这是其优先报道领域之一。 她说,在周三终止她的时候,编辑们引用了重组。

香港联合管理局在一份声明中表示,《华尔街日报》采取这一立场的”并不孤单”,其他当选的董事会成员”受到雇主的压力要求下台”。”此前,该杂志在香港的管理层告诉其现在前任记者之一,科技记者Dan Strumpf,不要竞选香港外国记者俱乐部的总裁,理由是公司面临风险。

香港记者协会仍然是一个声音团体,提倡在香港的本地和外国记者。 在本月早些时候的一篇文章中,中国国家喉舌《环球时报》称,它有”与分离主义政客勾结并在香港煽动骚乱的参差不齐的历史”,”绝不是代表香港媒体的专业”

《环球时报》强调了郑成功对《华尔街日报》的报道,称该报道攻击了《国家安全法》,以及另外两名董事会成员的报道:加拿大《环球邮报》(Globe And Mail)记者詹姆斯*格里菲斯(James Griffiths)和《华盛顿邮报》(Washington Post)前雇员的自由职业者西奥多拉*于(Theodora Yu)。

香港保安局局长唐炳强也攻击了香港联合行政当局,称它在2019年的抗议活动中与”黑衣暴力暴徒”站在一起。

香港记者协会在声明中呼吁所有在中国工作的媒体”允许其雇员自由倡导新闻自由和更好的工作条件,以声援香港和中国的记者同胞。”

原文如下

Wall Street Journal fires Hong Kong reporter who headed embattled press club

The Hong Kong Journalists Association has been accused in recent weeks by state-run media outlets in Hong Kong and China of destabilizing the city.

4 min

Selina Cheng, the newly elected chair of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, spoke to reporters after her employment contract with the Wall Street Journal was terminated, in Hong Kong on Wednesday. (Tyrone Siu/Reuters)

By Shibani Mahtani

Updated July 17, 2024 at 8:28 a.m. EDT|Published July 17, 2024 at 7:52 a.m. EDT

A Hong Kong-based reporter for the Wall Street Journal was terminated by the newspaper soon after she was elected as chair of the Hong Kong Journalists Association.

The HKJA, a press advocacy association, has been accused in recent weeks by state-backed and state-run media outlets in Hong Kong and China of destabilizing the city.

Selina Cheng, the reporter, said in a news conference Wednesday that she believes the termination is related to her role as chair of the organization. She said she came under pressure from her employer to quit the association.

The day before the HKJA election, Cheng said, her supervisors directed her to withdraw her candidacy and to leave HKJA’s board, of which she has been a member since 2021. She declined their requests.

“[I] was immediately told it would be incompatible with my job,” said Cheng. “The editor said employees of the Journal should not be seen as advocating for press freedom in a place like Hong Kong, even though they can in Western countries, where it is already established.”

The HKJA is considered a trade union, and under Hong Kong law, it is legal to be an officer of a union, a right guaranteed by the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

📰

Follow Media industry

In an emailed response, a spokesman for Dow Jones, the parent company of the Wall Street Journal, confirmed it made “personnel changes” on Wednesday but said it could not comment on specific individuals.

“The Wall Street Journal has been and continues to be a fierce and vocal advocate for press freedom in Hong Kong and around the world,” the spokesman added.

The termination, if linked to Cheng’s position at HKJA, would be the latest indication of how even large, well-resourced international media organizations are wary about the risks of operating in Hong Kong, a once-freewheeling city that has increasingly come to resemble mainland China in its suppression of civil liberties, including press freedom.

In the wake of mass protests in 2019, Beijing passed a national security law in Hong Kong that established punishments of up to life imprisonment for vaguely described crimes, such as subversion of state power and colluding with foreign forces.

These laws, alongside a new set of domestically focused national security laws passed this year, have had the effect of altering every institution in Hong Kong, from the courts to universities and newsrooms. After the passage of the national security law, the New York Times relocated its Hong Kong digital operation to Seoul, saying there was “a lot of uncertainty” about what the changes would mean for its operations and journalism.

Earlier this year, the Wall Street Journal said it was shifting its Asia headquarters from Hong Kong to Singapore and laid off a number of Hong Kong-based reporters. Cheng’s role was not affected at the time, and she continued to be based in and employed in the city. Cheng, 32, covered the Chinese auto industry, which the Journal has said is one of its priority coverage areas. In terminating her on Wednesday, editors cited restructuring, she said.

In a statement, the HKJA said the Journal is “not alone” in taking this stance and that other elected board members have been “pressured by their employers to stand down.” Previously, the Journal’s management in Hong Kong told one of its now-former reporters, technology reporter Dan Strumpf, not to run for president of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Hong Kong, citing risks to the company.

The HKJA remains a vocal group advocating for journalists in Hong Kong, both local and foreign. In a piece earlier this month, the Global Times, a Chinese state mouthpiece, said it had a “spotty history of colluding with separatist politicians and instigating riots in Hong Kong” and was “by no means a professional organization representing the Hong Kong media.”

The Global Times highlighted Cheng’s reporting for the Journal, which it said attacked the national security law, and the reporting of two other board members: James Griffiths, a correspondent for the Canadian-based Globe and Mail, and Theodora Yu, a freelancer who was a former employee of The Washington Post.

Hong Kong security chief Chris Tang Ping-keung has also attacked the HKJA, saying it had stood with the “black-clad violent mob” during the 2019 protests.

In its statement, the HKJA called on all media outlets working in China “to allow their employees to freely advocate for press freedom and better working conditions in solidarity with fellow journalists in Hong Kong and China.”